*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

We refuse to pay to protest!

Women's March on the Pentagon, October 2018

For Immediate Release

Contact: CindySheehan@MarchonPentagon.com

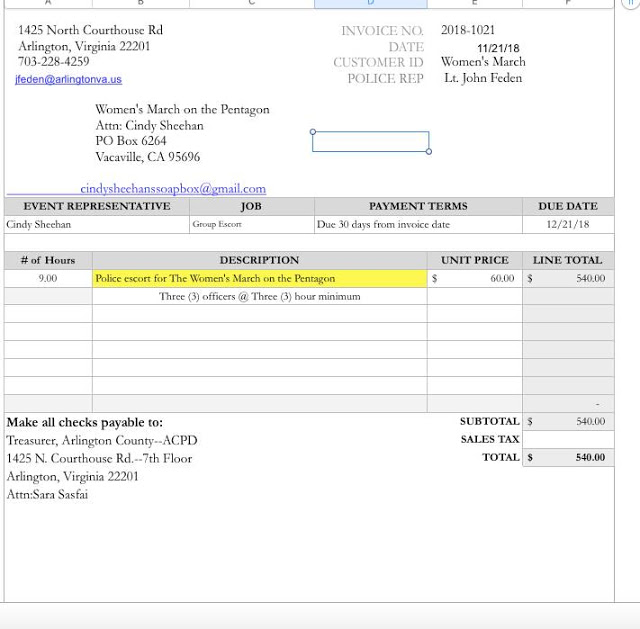

What: The day before Thanksgiving, Cindy Sheehan, co-coordinator of the recent Women's March on the Pentagon (WMOP) was presented with a $540.00 gill for "police escort" by the Arlington County Virginia Police Department (ACPD).

Background: Beginning in July, leadership of WMOP began taking steps to secure permits from the two jurisdictions that the WMOP would take on October 21st (51st anniversary of the March on the Pentagon during the Vietnam War):

Arlington County (brief march) and the Pentagon. Although WMOP eventually obtained a permit from the Pentagon, WMOP was never able to obtain a permit from Arlington County and many phone messages left by DC area Co-ordinator Malachy Kilbride were never returned by the ACPD.

On the day of the March, about 1500 people gathered at the Pentagon City Metro station (for a 12pm March start) in front of the mall and at about 10:30am, to the surprise of March organizers, ACPD showed up and did stop traffic for the brief March through Arlington County.

The organizers of the WMOP are outraged and appalled by this obvious violation of our First Amendment rights to gather “peaceably” and demonstrate one of the sacrosanct rights to our Freedom of Speech.

The DC area co-ordinator for the WMOP Malachy Kilbride had this to say upon receipt of the bill: “As a former resident of Arlington County of over 20 years I am disturbed that the county is following in the footsteps of the Trump Administration which wants to charge people for First Amendment activity. Shame on Arlington County! The First Amendment is priceless and shouldn’t be monetized.”

The Partnership for Civil Justice Fund (PCJF)* the D.C. based non-profit legal organization that works to protect and advance the constitutional rights of protestors has issued the following letter to the ACPD on behalf of the Women’s March on the Pentagon:

Chief Jay Farr

Lt. John Feden

Arlington County Police Department

1425 North Courthouse Rd

. Arlington, VA 22201

Dear Chief Farr and Lt. Feden:

We are writing on behalf of Cindy Sheehan in response to Lt. John Feden’s e-mail correspondence dated November 21, 2018.

The Arlington County Police Department (ACPD) has issued an invoice to Ms. Sheehan seeking to charge her for engaging in constitutionally protected First Amendment activities. Specifically, the invoice is stated to be “for the police services we provided October 21st during the March On the Pentagon,” and demands $540.00 for what is described as “police escort for The Women’s March on the Pentagon.”

This attempt to tax free speech is without lawful basis and violates Ms. Sheehan’s constitutional rights. We request that this invoice be immediately withdrawn.

Ms. Sheehan did not request police “services,” nor was she given prior notice that the ACPD intended to send police to the demonstration and charge her for their time. At no time did Ms. Sheehan agree to pay for any such charges.

Indeed, the ACPD actually refused to respond to Ms. Sheehan’s efforts to coordinate the First Amendment activities with them. An application for a permit was submitted for the March and thereafter, Arlington Country was nonresponsive to follow up efforts. After failing and refusing to return phone calls regarding the March, the ACDP appeared at the Pentagon City mall in front of the metro stop entrance at the starting point for the march, well before the march was scheduled to step off. At that time Ms. Sheehan expressed her surprise at their presence given their refusal to communicate with the March organizers.

The ACPD may not charge demonstrators for First Amendment activities at its own discretion. We are requesting that the ACPD provide all policy documents, guidelines, and criteria that the department relies upon in assessing charges on demonstration activities as well as any notice it believes was given to Ms. Sheehan of such policies and procedures.

We further request that the ACPD issue instructions to personnel consistent with constitutional obligations to ensure that organizers of demonstration activity are not improperly charged in the future.

Sincerely,

Mara Verheyden-Hilliard (PCJF)

The Women’s March on the Pentagon adamantly refuses to pay for this appalling violation of our constitutional rights.

*The Partnership for Civil Justice Fund is a free speech and civil rights organization that has defended First Amendment rights for over 20 years in Washington, D.C. and around the country. It is currently challenging the Trump Administration’s proposed anti-protest rules that would levy potentially bankrupting fees and costs on demonstrators who engage in constitutionally protected free speech on public parkland in the nation’s capital. More information here.

*(Women’s) March on the Pentagon is a women-led coalition of activists, professionals, military veterans, and everyday citizens of the world with one thing in common: we are anti-imperialist. More info can be found here.

This press release can also be found on our website:

https://marchonpentagon.com/we-refuse-pay-protest/

Join the Facebook group:

https://www.facebook.com/groups/183987719112273/

We refuse to pay to protest!

Women's March on the Pentagon, October 2018

For Immediate Release

Contact: CindySheehan@MarchonPentagon.com

What: The day before Thanksgiving, Cindy Sheehan, co-coordinator of the recent Women's March on the Pentagon (WMOP) was presented with a $540.00 gill for "police escort" by the Arlington County Virginia Police Department (ACPD).

Background: Beginning in July, leadership of WMOP began taking steps to secure permits from the two jurisdictions that the WMOP would take on October 21st (51st anniversary of the March on the Pentagon during the Vietnam War):

Arlington County (brief march) and the Pentagon. Although WMOP eventually obtained a permit from the Pentagon, WMOP was never able to obtain a permit from Arlington County and many phone messages left by DC area Co-ordinator Malachy Kilbride were never returned by the ACPD.

On the day of the March, about 1500 people gathered at the Pentagon City Metro station (for a 12pm March start) in front of the mall and at about 10:30am, to the surprise of March organizers, ACPD showed up and did stop traffic for the brief March through Arlington County.

The organizers of the WMOP are outraged and appalled by this obvious violation of our First Amendment rights to gather “peaceably” and demonstrate one of the sacrosanct rights to our Freedom of Speech.

The DC area co-ordinator for the WMOP Malachy Kilbride had this to say upon receipt of the bill: “As a former resident of Arlington County of over 20 years I am disturbed that the county is following in the footsteps of the Trump Administration which wants to charge people for First Amendment activity. Shame on Arlington County! The First Amendment is priceless and shouldn’t be monetized.”

The Partnership for Civil Justice Fund (PCJF)* the D.C. based non-profit legal organization that works to protect and advance the constitutional rights of protestors has issued the following letter to the ACPD on behalf of the Women’s March on the Pentagon:

Chief Jay Farr

Lt. John Feden

Arlington County Police Department

1425 North Courthouse Rd

. Arlington, VA 22201

Dear Chief Farr and Lt. Feden:

We are writing on behalf of Cindy Sheehan in response to Lt. John Feden’s e-mail correspondence dated November 21, 2018.

The Arlington County Police Department (ACPD) has issued an invoice to Ms. Sheehan seeking to charge her for engaging in constitutionally protected First Amendment activities. Specifically, the invoice is stated to be “for the police services we provided October 21st during the March On the Pentagon,” and demands $540.00 for what is described as “police escort for The Women’s March on the Pentagon.”

This attempt to tax free speech is without lawful basis and violates Ms. Sheehan’s constitutional rights. We request that this invoice be immediately withdrawn.

Ms. Sheehan did not request police “services,” nor was she given prior notice that the ACPD intended to send police to the demonstration and charge her for their time. At no time did Ms. Sheehan agree to pay for any such charges.

Indeed, the ACPD actually refused to respond to Ms. Sheehan’s efforts to coordinate the First Amendment activities with them. An application for a permit was submitted for the March and thereafter, Arlington Country was nonresponsive to follow up efforts. After failing and refusing to return phone calls regarding the March, the ACDP appeared at the Pentagon City mall in front of the metro stop entrance at the starting point for the march, well before the march was scheduled to step off. At that time Ms. Sheehan expressed her surprise at their presence given their refusal to communicate with the March organizers.

The ACPD may not charge demonstrators for First Amendment activities at its own discretion. We are requesting that the ACPD provide all policy documents, guidelines, and criteria that the department relies upon in assessing charges on demonstration activities as well as any notice it believes was given to Ms. Sheehan of such policies and procedures.

We further request that the ACPD issue instructions to personnel consistent with constitutional obligations to ensure that organizers of demonstration activity are not improperly charged in the future.

Sincerely,

Mara Verheyden-Hilliard (PCJF)

The Women’s March on the Pentagon adamantly refuses to pay for this appalling violation of our constitutional rights.

*The Partnership for Civil Justice Fund is a free speech and civil rights organization that has defended First Amendment rights for over 20 years in Washington, D.C. and around the country. It is currently challenging the Trump Administration’s proposed anti-protest rules that would levy potentially bankrupting fees and costs on demonstrators who engage in constitutionally protected free speech on public parkland in the nation’s capital. More information here.

*(Women’s) March on the Pentagon is a women-led coalition of activists, professionals, military veterans, and everyday citizens of the world with one thing in common: we are anti-imperialist. More info can be found here.

This press release can also be found on our website:

https://marchonpentagon.com/we-refuse-pay-protest/

Join the Facebook group:

https://www.facebook.com/groups/183987719112273/

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

America has spent $5.9 trillion on wars in the Middle East and Asia since 2001, a new study says

- The U.S. wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria and Pakistan have cost American taxpayers $5.9 trillion since they began in 2001.

- The figure reflects the cost across the U.S. federal government since the price of war is not borne by the Defense Department alone.

- The report also finds that more than 480,000 people have died from the wars and more than 244,000 civilians have been killed as a result of fighting. Additionally, another 10 million people have been displaced due to violence.

- https://www.cnbc.com/2018/11/14/us-has-spent-5point9-trillion-on-middle-east-asia-wars-since-2001-study.html

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

- The U.S. wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria and Pakistan have cost American taxpayers $5.9 trillion since they began in 2001.

- The figure reflects the cost across the U.S. federal government since the price of war is not borne by the Defense Department alone.

- The report also finds that more than 480,000 people have died from the wars and more than 244,000 civilians have been killed as a result of fighting. Additionally, another 10 million people have been displaced due to violence.

- https://www.cnbc.com/2018/11/14/us-has-spent-5point9-trillion-on-middle-east-asia-wars-since-2001-study.html

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Open letter to active duty soldiers on the border

DON'T TURN THEM AWAY

THE MIGRANTS IN THE CENTRAL AMERICAN CARAVAN ARE NOT OUR ENEMIES

Your Commander-in-chief is lying to you. You should refuse his orders to deploy to the southern U.S. border should you be called to do so. Despite what Trump and his administration are saying, the migrants moving North towards the U.S. are not a threat. These small numbers of people are escaping intense violence. In fact, much of the reason these men and women—with families just like yours and ours—are fleeing their homes is because of the US meddling in their country's elections. Look no further than Honduras, where the Obama administration supported the overthrow of a democratically elected president who was then replaced by a repressive dictator.

Courage to Resist has been running a strategic outreach campaign to challenge troops to refuse illegal orders while on the border, such as their Commander-in-Chief's suggestion that they murder migrants who might be throwing rocks, or that they build and help run concentration camps. In addition to social media ads, About Face, Veterans For Peace, and Courage to Resist, are also printing tens of thousands of these leaflets for distribution near the border. Please consider donating towards these expenses.

Open letter to active duty soldiers on the border

DON'T TURN THEM AWAY

THE MIGRANTS IN THE CENTRAL AMERICAN CARAVAN ARE NOT OUR ENEMIES

THE MIGRANTS IN THE CENTRAL AMERICAN CARAVAN ARE NOT OUR ENEMIES

Your Commander-in-chief is lying to you. You should refuse his orders to deploy to the southern U.S. border should you be called to do so. Despite what Trump and his administration are saying, the migrants moving North towards the U.S. are not a threat. These small numbers of people are escaping intense violence. In fact, much of the reason these men and women—with families just like yours and ours—are fleeing their homes is because of the US meddling in their country's elections. Look no further than Honduras, where the Obama administration supported the overthrow of a democratically elected president who was then replaced by a repressive dictator.

Courage to Resist has been running a strategic outreach campaign to challenge troops to refuse illegal orders while on the border, such as their Commander-in-Chief's suggestion that they murder migrants who might be throwing rocks, or that they build and help run concentration camps. In addition to social media ads, About Face, Veterans For Peace, and Courage to Resist, are also printing tens of thousands of these leaflets for distribution near the border. Please consider donating towards these expenses.

Don't turn them away

The migrants in the Central American caravan are not our enemies

Open letter to active duty soldiers

Your Commander-in-chief is lying to you. You should refuse his orders to deploy to the southern U.S. border should you be called to do so. Despite what Trump and his administration are saying, the migrants moving North towards the U.S. are not a threat. These small numbers of people are escaping intense violence. In fact, much of the reason these men and women—with families just like yours and ours—are fleeing their homes is because of the US meddling in their country's elections. Look no further than Honduras, where the Obama administration supported the overthrow of a democratically elected president who was then replaced by a repressive dictator.

"There are tens of thousands of us who will support your decision to lay your weapons down. You are better than your Commander-in-chief. Our only advice is to resist in groups. Organize with your fellow soldiers. Do not go this alone."

These extremely poor and vulnerable people are desperate for peace. Who among us would walk a thousand miles with only the clothes on our back without great cause? The odds are good that your parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, etc. lived similar experiences to these migrants. Your family members came to the U.S. to seek a better life—some fled violence. Consider this as you are asked to confront these unarmed men, women and children from Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador. To do so would be the ultimate hypocrisy.

The U.S. is the richest country in the world, in part because it has exploited countries in Latin America for decades. If you treat people from these countries like criminals, as Trump hopes you will, you only contribute to the legacy of pillage and plunder beneath our southern border. We need to confront this history together, we need to confront the reality of America's wealth and both share and give it back with these people. Above all else, we cannot turn them away at our door. They will die if we do.

By every moral or ethical standard it is your duty to refuse orders to "defend" the U.S. from these migrants. History will look kindly upon you if you do. There are tens of thousands of us who will support your decision to lay your weapons down. You are better than your Commander-in-chief. Our only advice is to resist in groups. Organize with your fellow soldiers. Do not go this alone. It is much harder to punish the many than the few.

In solidarity,

Rory Fanning

Former U.S. Army Ranger, War-Resister

Spenser Rapone

Former U.S. Army Ranger and Infantry Officer, War-Resister

Leaflet distributed by:

-

About Face: Veterans Against the War

-

Courage to Resist

-

Veterans For Peace

Courage to Resist has been running a strategic outreach campaign to challenge troops to refuse illegal orders while on the border, such as their Commander-in-Chief's suggestion that they murder migrants who might be throwing rocks, or that they build and help run concentration camps. In addition to social media ads, About Face, Veterans For Peace, and Courage to Resist, are also printing tens of thousands of these leaflets for distribution near the border. Please consider donating towards these expenses.

COURAGE TO RESIST ~ SUPPORT THE TROOPS WHO REFUSE TO FIGHT!

484 Lake Park Ave #41, Oakland, California 94610 ~ 510-488-3559

www.couragetoresist.org ~ facebook.com/couragetoresist*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

COURAGE TO RESIST

New "Refuse War" Shirts

We've launched a new shirt store to raise funds to support war resisters.

In addition to the Courage to Resist logo shirts we've offered in the past, we now have a few fun designs, including a grim reaper, a "Refuse War, Go AWOL" travel theme, and a sporty "AWOL: Support Military War Resisters" shirt.

Shirts are $25 each for small through XL, and bit more for larger sizes. Please allow 9-12 days for delivery within the United States.

50% of each shirt may qualify as a tax-deductible contribution.

Courage to Resist -- Support the Troops who Refuse to Fight!

484 Lake Park Ave. #41, Oakland, CA 94610, 510-488-3559

couragetoresis.org -- facebook.com/couragetoresist

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Open letter to active duty soldiers

Your Commander-in-chief is lying to you. You should refuse his orders to deploy to the southern U.S. border should you be called to do so. Despite what Trump and his administration are saying, the migrants moving North towards the U.S. are not a threat. These small numbers of people are escaping intense violence. In fact, much of the reason these men and women—with families just like yours and ours—are fleeing their homes is because of the US meddling in their country's elections. Look no further than Honduras, where the Obama administration supported the overthrow of a democratically elected president who was then replaced by a repressive dictator.

"There are tens of thousands of us who will support your decision to lay your weapons down. You are better than your Commander-in-chief. Our only advice is to resist in groups. Organize with your fellow soldiers. Do not go this alone."

These extremely poor and vulnerable people are desperate for peace. Who among us would walk a thousand miles with only the clothes on our back without great cause? The odds are good that your parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, etc. lived similar experiences to these migrants. Your family members came to the U.S. to seek a better life—some fled violence. Consider this as you are asked to confront these unarmed men, women and children from Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador. To do so would be the ultimate hypocrisy.

The U.S. is the richest country in the world, in part because it has exploited countries in Latin America for decades. If you treat people from these countries like criminals, as Trump hopes you will, you only contribute to the legacy of pillage and plunder beneath our southern border. We need to confront this history together, we need to confront the reality of America's wealth and both share and give it back with these people. Above all else, we cannot turn them away at our door. They will die if we do.

By every moral or ethical standard it is your duty to refuse orders to "defend" the U.S. from these migrants. History will look kindly upon you if you do. There are tens of thousands of us who will support your decision to lay your weapons down. You are better than your Commander-in-chief. Our only advice is to resist in groups. Organize with your fellow soldiers. Do not go this alone. It is much harder to punish the many than the few.

In solidarity,

Rory Fanning

Former U.S. Army Ranger, War-Resister Spenser Rapone Former U.S. Army Ranger and Infantry Officer, War-Resister

Leaflet distributed by:

Courage to Resist has been running a strategic outreach campaign to challenge troops to refuse illegal orders while on the border, such as their Commander-in-Chief's suggestion that they murder migrants who might be throwing rocks, or that they build and help run concentration camps. In addition to social media ads, About Face, Veterans For Peace, and Courage to Resist, are also printing tens of thousands of these leaflets for distribution near the border. Please consider donating towards these expenses.

|

COURAGE TO RESIST ~ SUPPORT THE TROOPS WHO REFUSE TO FIGHT!

484 Lake Park Ave #41, Oakland, California 94610 ~ 510-488-3559

www.couragetoresist.org ~ facebook.com/couragetoresist*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

484 Lake Park Ave #41, Oakland, California 94610 ~ 510-488-3559

www.couragetoresist.org ~ facebook.com/couragetoresist*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

COURAGE TO RESIST

New "Refuse War" Shirts

We've launched a new shirt store to raise funds to support war resisters.

In addition to the Courage to Resist logo shirts we've offered in the past, we now have a few fun designs, including a grim reaper, a "Refuse War, Go AWOL" travel theme, and a sporty "AWOL: Support Military War Resisters" shirt.

Shirts are $25 each for small through XL, and bit more for larger sizes. Please allow 9-12 days for delivery within the United States.

50% of each shirt may qualify as a tax-deductible contribution.

In addition to the Courage to Resist logo shirts we've offered in the past, we now have a few fun designs, including a grim reaper, a "Refuse War, Go AWOL" travel theme, and a sporty "AWOL: Support Military War Resisters" shirt.

Shirts are $25 each for small through XL, and bit more for larger sizes. Please allow 9-12 days for delivery within the United States.

50% of each shirt may qualify as a tax-deductible contribution.

Courage to Resist -- Support the Troops who Refuse to Fight!

484 Lake Park Ave. #41, Oakland, CA 94610, 510-488-3559

couragetoresis.org -- facebook.com/couragetoresist

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Judge to Soon Rule on Mumia’s Appeal Bid

By Kyle Fraser, December 4, 2018

Philadelphia Common Pleas Judge Leon Tucker promised a decision on whether a former prosecutor unlawfully took part as a judge in rejecting Mumia Abu Jamal’s appeal of his 1981 conviction in the killing of a police officer. “We’re not going to stop fighting until we see Mumia walk out of these prison walls,” said Johanna Fernandez, of the Campaign to Bring Mumia Home. Pam Africa, of the MOVE organization, said Abu Jamal’s supporters have sustained his defense for decades “no matter what kind of devious tricks this government has used to try to break this movement.”

Listen to a radio report at Black Agenda Report:

https://www.blackagendareport.com/judge-soon-rule-mumias-appeal-bid

Free Mumia Now!

Mumia's freedom is at stake in a court hearing on August 30th.

With your help, we just might free him!

Check out this video:

This video includes photo of 1996 news report refuting Judge Castille's present assertion that he had not been requested at that time to recuse himself from this case, on which he had previously worked as a Prosecutor:

A Philadelphia court now has before it the evidence which could lead to Mumia's freedom. The evidence shows that Ronald Castille, of the District Attorney's office in 1982, intervened in the prosecution of Mumia for a crime he did not commit. Years later, Castille was a judge on the PA Supreme Court, where he sat in judgement over Mumia's case, and ruled against Mumia in every appeal!

According to the US Supreme Court in the Williams ruling, this corrupt behavior was illegal!

But will the court rule to overturn all of Mumia's negative appeals rulings by the PA Supreme Court? If it does, Mumia would be free to appeal once again against his unfair conviction. If it does not, Mumia could remain imprisoned for life, without the possibility for parole, for a crime he did not commit.

• Mumia Abu-Jamal is innocent and framed!

• Mumia Abu-Jamal is a journalist censored off the airwaves!

• Mumia Abu-Jamal is victimized by cops, courts and politicians!

• Mumia Abu-Jamal stands for all prisoners treated unjustly!

• Courts have never treated Mumia fairly!

Will You Help Free Mumia?

Call DA Larry Krasner at (215) 686-8000

Tell him former DA Ron Castille violated Mumia's constitutional rights and

Krasner should cease opposing Mumia's legal petition.

Tell the DA to release Mumia because he's factually innocent.

Write to Mumia at:

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

A Call for a Mass Mobilization to Oppose NATO, War and Racism

Protest NATO, Washington, DC, Lafayette Park (across from the White House)

1 PM Saturday, March 30, 2019.

Additional actions will take place on Thursday April 4 at the opening of the NATO meeting

April 4, 2019, will mark the 51st anniversary of the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., the internationally revered leader in struggles against racism, poverty and war.

And yet, in a grotesque desecration of Rev. King's lifelong dedication to peace, this is the date that the military leaders of the North American Treaty Organization have chosen to celebrate NATO's 70th anniversary by holding its annual summit meeting in Washington, D.C. This is a deliberate insult to Rev. King and a clear message that Black lives and the lives of non-European humanity really do not matter.

It was exactly one year before he was murdered that Rev. King gave his famous speech opposing the U.S. war in Vietnam, calling the U.S. government "the greatest purveyor of violence in the world" and declaring that he could not be silent.

We cannot be silent either. Since its founding, the U.S.-led NATO has been the world's deadliest military alliance, causing untold suffering and devastation throughout Northern Africa, the Middle East and beyond.

Hundreds of thousands have died in U.S./NATO wars in Iraq, Libya, Somalia and Yugoslavia. Millions of refugees are now risking their lives trying to escape the carnage that these wars have brought to their homelands, while workers in the 29 NATO member-countries are told they must abandon hard-won social programs in order to meet U.S. demands for even more military spending.

Every year when NATO holds its summits, there have been massive protests: in Chicago, Wales, Warsaw, Brussels. 2019 will be no exception.

The United National Antiwar Coalition (UNAC) is calling for a mass mobilization in Washington, D.C., on Saturday, March 30. Additional actions will take place on April 4 at the opening of the NATO meeting.

We invite you to join with us in this effort. As Rev. King taught us, "Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter."

No to NATO!

End All U.S. Wars at Home and Abroad!

Bring the Troops Home Now!

No to Racism!

The Administrative Committee of UNAC,

To add your endorsement to this call, please go here: http://www.no2nato2019.org/endorse-the-action.html

Please donate to keep UNAC strong: https://www.unacpeace.org/donate.html

If your organization would like to join the UNAC coalition, please click here: https://www.unacpeace.org/join.html

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

In Defense of Kevin "Rashid" Johnson

Update on Rashid in Indiana

By Dustin McDaniel

November 9, 2018—Had a call with Rashid yesterday. He's been seen by medical, psych, and

dental. He's getting his meds and his blood pressure is being monitored,

though it is uncontrolled. The RN made recommendations for treatment

that included medication changes and further monitoring, but there's

been no follow up.

He's at the diagnostic center and he (along with everyone else I've

talked to about it) expect that he'll be sent to the solitary

confinement unit at Wabash Valley Correctional Facility, though it could

be 30 days from now.

He's in a cell with no property. He has no extra underwear to change

into. The cell is, of course, dirty. He's in solitary confinement. He

didn't say they were denying him yard time. He didn't say there were any

problems with his meals.

They are refusing him his stationary and stamps, so he can't write out.

He gets a very limited number of phone calls per month (1 or 2), and

otherwise can only talk on the phone if a legal call is set up.

They are refusing to give him his property, or to allow him to look

through it to find records relevant to ongoing or planned litigation.

He's already past the statute of limitations on a law suit he planned to

file re abuses in Texas and other deadlines are about to pass over the

next month.

He has 35 banker boxes of property, or 2 pallets, that arrived in IDOC.

He needs to be allowed to look through these records in order to find

relevant legal documents. Moving forward, I think we need to find a

place/person for him to send these records to or they are going to be

destroyed. It would be good if we could find someone who would also take

on the task of organizing the records, getting rid of duplicates or

unnecessary paperwork, digitizing records, and making things easier to

search and access.

Although he does not appear in the inmate locator for IDOC, he does

appears in the JPay system as an Indiana prisoner (#264847). At his

request, I sent him some of his money so hopefully he can get stamps and

stationary.

Hold off on sending him more money via JPay - I've been told that some

of the IDOC facilities are phasing out JPay and moving to GTL and

wouldn't want to have a bunch of money stuck and inaccessible due to

those changes. If you want to send him more money immediately, send it

to Abolitionist Law Center. You can send it via Paypal to

info@abolitionistlawcenter.org, or mail it to PO Box 8654, Pittsburgh,

PA 15221. We will hold on to it and distribute it according to Rashid's

instructions.

Please write to him, if you haven't already. He's got nothing to do in

solitary with nothing to read and nothing to write with.

FOR UPDATES CHECK OUT RASHID'S WEBSITE AT RASHIDMOD.COM

you can also hear a recent interview with Rashid on Final Straw podcast here: https://thefinalstrawradio.noblogs.org/post/tag/kevin-rashid-johnson/

Write to Rashid:

Kevin Rashid Johnson's writings and artwork have been widely circulated. He is the author of a book,Panther Vision: Essential Party Writings and Art of Kevin "Rashid" Johnson, Minister of Defense, New Afrikan Black Panther Party, (Kersplebedeb, 2010).

Kevin Johnson D.O.C. No. 264847

G-20-2C Pendleton Correctional Facility

4490 W. Reformatory Rd.

Pendleton, IN 46064-9001

www.rashidmod.com

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Judge to Soon Rule on Mumia’s Appeal Bid

By Kyle Fraser, December 4, 2018

Philadelphia Common Pleas Judge Leon Tucker promised a decision on whether a former prosecutor unlawfully took part as a judge in rejecting Mumia Abu Jamal’s appeal of his 1981 conviction in the killing of a police officer. “We’re not going to stop fighting until we see Mumia walk out of these prison walls,” said Johanna Fernandez, of the Campaign to Bring Mumia Home. Pam Africa, of the MOVE organization, said Abu Jamal’s supporters have sustained his defense for decades “no matter what kind of devious tricks this government has used to try to break this movement.”

Listen to a radio report at Black Agenda Report:

https://www.blackagendareport.com/judge-soon-rule-mumias-appeal-bid

Free Mumia Now!

Mumia's freedom is at stake in a court hearing on August 30th.

With your help, we just might free him!

Check out this video:

This video includes photo of 1996 news report refuting Judge Castille's present assertion that he had not been requested at that time to recuse himself from this case, on which he had previously worked as a Prosecutor:

A Philadelphia court now has before it the evidence which could lead to Mumia's freedom. The evidence shows that Ronald Castille, of the District Attorney's office in 1982, intervened in the prosecution of Mumia for a crime he did not commit. Years later, Castille was a judge on the PA Supreme Court, where he sat in judgement over Mumia's case, and ruled against Mumia in every appeal!

According to the US Supreme Court in the Williams ruling, this corrupt behavior was illegal!

But will the court rule to overturn all of Mumia's negative appeals rulings by the PA Supreme Court? If it does, Mumia would be free to appeal once again against his unfair conviction. If it does not, Mumia could remain imprisoned for life, without the possibility for parole, for a crime he did not commit.

• Mumia Abu-Jamal is innocent and framed!

• Mumia Abu-Jamal is a journalist censored off the airwaves!

• Mumia Abu-Jamal is victimized by cops, courts and politicians!

• Mumia Abu-Jamal stands for all prisoners treated unjustly!

• Courts have never treated Mumia fairly!

Will You Help Free Mumia?

Call DA Larry Krasner at (215) 686-8000

Tell him former DA Ron Castille violated Mumia's constitutional rights and

Krasner should cease opposing Mumia's legal petition.

Tell the DA to release Mumia because he's factually innocent.

Write to Mumia at:

Smart Communications/PA DOC

SCI Mahanoy

Mumia Abu-Jamal #AM-8335

P.O. Box 33028

St. Petersburg, FL 33733

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

A Call for a Mass Mobilization to Oppose NATO, War and Racism

Protest NATO, Washington, DC, Lafayette Park (across from the White House)

1 PM Saturday, March 30, 2019.

Additional actions will take place on Thursday April 4 at the opening of the NATO meeting

April 4, 2019, will mark the 51st anniversary of the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., the internationally revered leader in struggles against racism, poverty and war.

And yet, in a grotesque desecration of Rev. King's lifelong dedication to peace, this is the date that the military leaders of the North American Treaty Organization have chosen to celebrate NATO's 70th anniversary by holding its annual summit meeting in Washington, D.C. This is a deliberate insult to Rev. King and a clear message that Black lives and the lives of non-European humanity really do not matter.

It was exactly one year before he was murdered that Rev. King gave his famous speech opposing the U.S. war in Vietnam, calling the U.S. government "the greatest purveyor of violence in the world" and declaring that he could not be silent.

We cannot be silent either. Since its founding, the U.S.-led NATO has been the world's deadliest military alliance, causing untold suffering and devastation throughout Northern Africa, the Middle East and beyond.

Hundreds of thousands have died in U.S./NATO wars in Iraq, Libya, Somalia and Yugoslavia. Millions of refugees are now risking their lives trying to escape the carnage that these wars have brought to their homelands, while workers in the 29 NATO member-countries are told they must abandon hard-won social programs in order to meet U.S. demands for even more military spending.

Every year when NATO holds its summits, there have been massive protests: in Chicago, Wales, Warsaw, Brussels. 2019 will be no exception.

The United National Antiwar Coalition (UNAC) is calling for a mass mobilization in Washington, D.C., on Saturday, March 30. Additional actions will take place on April 4 at the opening of the NATO meeting.

We invite you to join with us in this effort. As Rev. King taught us, "Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter."

No to NATO!

End All U.S. Wars at Home and Abroad!

Bring the Troops Home Now!

No to Racism!

The Administrative Committee of UNAC,

To add your endorsement to this call, please go here: http://www.no2nato2019.org/endorse-the-action.html

Please donate to keep UNAC strong: https://www.unacpeace.org/donate.html

If your organization would like to join the UNAC coalition, please click here: https://www.unacpeace.org/join.html

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

In Defense of Kevin "Rashid" Johnson

Update on Rashid in Indiana

By Dustin McDaniel

November 9, 2018—Had a call with Rashid yesterday. He's been seen by medical, psych, and

dental. He's getting his meds and his blood pressure is being monitored,

though it is uncontrolled. The RN made recommendations for treatment

that included medication changes and further monitoring, but there's

been no follow up.

He's at the diagnostic center and he (along with everyone else I've

talked to about it) expect that he'll be sent to the solitary

confinement unit at Wabash Valley Correctional Facility, though it could

be 30 days from now.

He's in a cell with no property. He has no extra underwear to change

into. The cell is, of course, dirty. He's in solitary confinement. He

didn't say they were denying him yard time. He didn't say there were any

problems with his meals.

They are refusing him his stationary and stamps, so he can't write out.

He gets a very limited number of phone calls per month (1 or 2), and

otherwise can only talk on the phone if a legal call is set up.

They are refusing to give him his property, or to allow him to look

through it to find records relevant to ongoing or planned litigation.

He's already past the statute of limitations on a law suit he planned to

file re abuses in Texas and other deadlines are about to pass over the

next month.

He has 35 banker boxes of property, or 2 pallets, that arrived in IDOC.

He needs to be allowed to look through these records in order to find

relevant legal documents. Moving forward, I think we need to find a

place/person for him to send these records to or they are going to be

destroyed. It would be good if we could find someone who would also take

on the task of organizing the records, getting rid of duplicates or

unnecessary paperwork, digitizing records, and making things easier to

search and access.

Although he does not appear in the inmate locator for IDOC, he does

appears in the JPay system as an Indiana prisoner (#264847). At his

request, I sent him some of his money so hopefully he can get stamps and

stationary.

Hold off on sending him more money via JPay - I've been told that some

of the IDOC facilities are phasing out JPay and moving to GTL and

wouldn't want to have a bunch of money stuck and inaccessible due to

those changes. If you want to send him more money immediately, send it

to Abolitionist Law Center. You can send it via Paypal to

info@abolitionistlawcenter.org, or mail it to PO Box 8654, Pittsburgh,

PA 15221. We will hold on to it and distribute it according to Rashid's

instructions.

Please write to him, if you haven't already. He's got nothing to do in

solitary with nothing to read and nothing to write with.

By Dustin McDaniel

November 9, 2018—Had a call with Rashid yesterday. He's been seen by medical, psych, and

dental. He's getting his meds and his blood pressure is being monitored,

though it is uncontrolled. The RN made recommendations for treatment

that included medication changes and further monitoring, but there's

been no follow up.

He's at the diagnostic center and he (along with everyone else I've

talked to about it) expect that he'll be sent to the solitary

confinement unit at Wabash Valley Correctional Facility, though it could

be 30 days from now.

He's in a cell with no property. He has no extra underwear to change

into. The cell is, of course, dirty. He's in solitary confinement. He

didn't say they were denying him yard time. He didn't say there were any

problems with his meals.

They are refusing him his stationary and stamps, so he can't write out.

He gets a very limited number of phone calls per month (1 or 2), and

otherwise can only talk on the phone if a legal call is set up.

They are refusing to give him his property, or to allow him to look

through it to find records relevant to ongoing or planned litigation.

He's already past the statute of limitations on a law suit he planned to

file re abuses in Texas and other deadlines are about to pass over the

next month.

He has 35 banker boxes of property, or 2 pallets, that arrived in IDOC.

He needs to be allowed to look through these records in order to find

relevant legal documents. Moving forward, I think we need to find a

place/person for him to send these records to or they are going to be

destroyed. It would be good if we could find someone who would also take

on the task of organizing the records, getting rid of duplicates or

unnecessary paperwork, digitizing records, and making things easier to

search and access.

Although he does not appear in the inmate locator for IDOC, he does

appears in the JPay system as an Indiana prisoner (#264847). At his

request, I sent him some of his money so hopefully he can get stamps and

stationary.

Hold off on sending him more money via JPay - I've been told that some

of the IDOC facilities are phasing out JPay and moving to GTL and

wouldn't want to have a bunch of money stuck and inaccessible due to

those changes. If you want to send him more money immediately, send it

to Abolitionist Law Center. You can send it via Paypal to

info@abolitionistlawcenter.org, or mail it to PO Box 8654, Pittsburgh,

PA 15221. We will hold on to it and distribute it according to Rashid's

instructions.

Please write to him, if you haven't already. He's got nothing to do in

solitary with nothing to read and nothing to write with.

FOR UPDATES CHECK OUT RASHID'S WEBSITE AT RASHIDMOD.COM

you can also hear a recent interview with Rashid on Final Straw podcast here: https://thefinalstrawradio.noblogs.org/post/tag/kevin-rashid-johnson/

Write to Rashid:

Kevin Rashid Johnson's writings and artwork have been widely circulated. He is the author of a book,Panther Vision: Essential Party Writings and Art of Kevin "Rashid" Johnson, Minister of Defense, New Afrikan Black Panther Party, (Kersplebedeb, 2010).

Kevin Johnson D.O.C. No. 264847

G-20-2C Pendleton Correctional Facility

4490 W. Reformatory Rd.

Pendleton, IN 46064-9001

www.rashidmod.com

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Prisoners at Lieber Correctional Institution in South Carolina are demanding recognition of their human rights by the South Carolina Department of Corrections and warden Randall Williams. Prisoners are also demanding an end to the horrific conditions they are forced to exist under at Lieber, which are exascerbating already rising tensions to a tipping point and people are dying.

Since the tragedy that occured at Lee Correctional earlier this year, prisoners at all level 3 security prisons in SC have been on complete lockdown, forced to stay in their two-man 9x11 cells 24 hours a day (supposed to be 23 hrs/day but guards rarely let prisoners go to their one hour of rec in a slightly larger cage because it requires too much work, especially when you keep an entire prison on lockdown) without any programming whatsoever and filthy air rushing in all day, no chairs, tables, no radios, no television, no access to legal work, no access to showers, and no light! Administration decided to cover all the tiny windows in the cells with metal plates on the outside so that no light can come in. Thousands of people are existing in this manner, enclosed in a tiny space with another person and no materials or communication or anything to pass the time.

Because of these horific conditions tensions are rising and people are dying. Another violent death took place at Lieber Correctional; Derrick Furtick, 31, died at approximately 9pm Monday, according to state Department of Corrections officials:

Prisoners assert that this death is a result of the kind of conditions that are being imposed and inflicted upon the incarcerated population there and the undue trauma, anxiety, and tensions these conditions create.

We demand:

- to be let off solitary confinement

- to have our windows uncovered

- access to books, magazines, phone calls, showers and recreation

- access to the law library and our legal cases

- single person cells for any person serving over 20 years

Lieber is known for its horrendous treatment of the people it cages including its failure to evacuate prisoners during Hurricane Florence earlier this year:

Please flood the phone lines of both the governor's and warden's offices to help amplify these demands from behind bars at Lieber Correctional.

Warden Randall Williams: (843) 875-3332 or (803) 896-3700

Governor Henry McMaster's office: (803) 734-2100

Status

Read in browser »

|

Recent Articles:

Get Involved

Support IWOC by connecting with the closest local, subscribing to the newsletter or making a donation.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Get Malik Out of Ad-Seg

Keith "Malik" Washington is an incarcerated activist who has spoken out on conditions of confinement in Texas prison and beyond: from issues of toxic water and extreme heat, to physical and sexual abuse of imprisoned people, to religious discrimination and more. Malik has also been a tireless leader in the movement to #EndPrisonSlavery which gained visibility during nationwide prison strikes in 2016 and 2018. View his work at comrademalik.com or write him at:

Keith H. Washington

TDC# 1487958

McConnell Unit

3001 S. Emily Drive

Beeville, TX 78102

Friends, it's time to get Malik out of solitary confinement.

Malik has experienced intense, targeted harassment ever since he dared to start speaking against brutal conditions faced by incarcerated people in Texas and nationwide--but over the past few months, prison officials have stepped up their retaliation even more.

In Administrative Segregation (solitary confinement) at McConnell Unit, Malik has experienced frequent humiliating strip searches, medical neglect, mail tampering and censorship, confinement 23 hours a day to a cell that often reached 100+ degrees in the summer, and other daily abuses too numerous to name. It could not be more clear that they are trying to make an example of him because he is a committed freedom fighter. So we have to step up.

Phone zap on Tuesday, November 13

**Mark your calendars for the 11/13 call in, be on the look out for a call script, and spread the word!!**

Demands:

- Convene special review of Malik's placement in Ad-Seg and immediately release him back to general population

- Explain why the State Classification Committee's decision to release Malik from Ad-Seg back in June was overturned (specifically, demand to know the nature of the "information" supposedly collected by the Fusion Center, and demand to know how this information was investigated and verified).

- Immediately cease all harassment and retaliation against Malik, especially strip searches and mail censorship!

Who to contact:

TDCJ Executive Director Bryan Collier

Phone: (936)295-6371

Email: exec.director@tdcj.texas.gov

Senior Warden Philip Sinfuentes (McConnell Unit)

Phone: (361) 362-2300

-------

Background on Malik's Situation

Malik's continued assignment to Ad-Seg (solitary confinement) in is an overt example of political repression, plain and simple. Prison officials placed Malik in Ad-Seg two years ago for writing about and endorsing the 2016 nationwide prison strike. They were able to do this because Texas and U.S. law permits non-violent work refusal to be classified as incitement to riot.

It gets worse. Malik was cleared for release from Ad-Seg by the State Classification Committee in June--and then, in an unprecedented reversal, immediately re-assigned him back to Ad-Seg. The reason? Prison Officials site "information" collected by a shadowy intelligence gathering operation called a Fusion Center, which are known for lack of transparency and accountability, and for being blatant tools of political repression.

Malik remains in horrible conditions, vulnerable to every possible abuse, on the basis of "information" that has NEVER been disclosed or verified. No court or other independent entity has ever confirmed the existence, let alone authenticity, of this alleged information. In fact, as recently as October 25, a representative of the State Classification Committee told Malik that he has no clue why Malik was re-assigned to Ad-Seg. This "information" is pure fiction.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

|

Listen to 'The Daily': Was Kevin Cooper Framed for Murder?

By Michael Barbaro, May 30, 2018

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/30/podcasts/the-daily/kevin-cooper-death-row.html?emc=edit_ca_20180530&nl=california-today&nlid=2181592020180530&te=1

Listen and subscribe to our podcast from your mobile device: Via Apple Podcasts | Via RadioPublic | Via Stitcher

The sole survivor of an attack in which four people were murdered identified the perpetrators as three white men. The police ignored suspects who fit the description and arrested a young black man instead. He is now awaiting execution.

On today's episode:

• Kevin Cooper, who has been on death row at San Quentin State Prison in California for three decades.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Last week I met with fellow organizers and members of Mijente to take joint action at the Tornillo Port of Entry, where detention camps have been built and where children and adults are currently being imprisoned.

I oppose the hyper-criminalization of migrants and asylum seekers. Migration is a human right and every person is worthy of dignity and respect irrespective of whether they have "papers" or not. You shouldn't have to prove "extreme and unusual hardship" to avoid being separated from your family. We, as a country, have a moral responsibility to support and uplift those adversely affected by the US's decades-long role in the economic and military destabilization of the home countries these migrants and asylum seekers have been forced to leave.

While we expected to face resistance and potential trouble from the multiple law enforcement agencies represented at the border, we didn't expect to have a local farm hand pull a pistol on us to demand we deflate our giant balloon banner. Its message to those in detention:

NO ESTÁN SOLOS (You are not alone).

Despite the slight disruption to our plan we were able to support Mijente and United We Dream in blocking the main entrance to the detention camp and letting those locked inside know that there are people here who care for them and want to see them free and reunited with their families.

We are continuing to stand in solidarity with Mijente as they fight back against unjust immigration practices.Yesterday they took action in San Diego, continuing to lead and escalate resistance to unjust detention, Attorney General Jeff Sessions and to ICE.

While we were honored to offer on-the-ground support we see the potential to focus the energy of our Drop the MIC campaign into fighting against this injustice, to have an even greater impact. Here's how:

- Call out General Dynamics for profiteering of War, Militarization of the Border and Child and Family Detention (look for our social media toolkit this week);

- Create speaking forums and produce media that challenges the narrative of ICE and Jeff Sessions, encouraging troops who have served in the borderlands to speak out about that experience;

- Continue to show up and demand we demilitarize the border and abolish ICE.

Thank you for your vision and understanding of how militarism, racism, and capitalism are coming together in the most destructive ways. Help keep us in this fight by continuing to support our work.

In Solidarity,

Ramon Mejia

Field Organizer, About Face: Veterans Against the War

P.O. Box 3565, New York, NY 10008. All Right Reserved. | Unsubscribe

To ensure delivery of About Face emails please add webmaster@ivaw.org to your address book.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Major George Tillery

MAJOR TILLERY FILES NEW LEGAL PETITION

SEX FOR LIES AND

MANUFACTURED TESTIMONY

April 25, 2018-- The arrest of two young men in Starbucks for the crime of "sitting while black," and the four years prison sentence to rapper Meek Mill for a minor parole violation are racist outrages in Philadelphia, PA that made national news in the past weeks. Yesterday Meek Mills was released on bail after a high profile defense campaign and a Pa Supreme Court decision citing evidence his conviction was based solely on a cop's false testimony.

These events underscore the racism, frame-up, corruption and brutality at the core of the criminal injustice system. Pennsylvania "lifer" Major Tillery's fight for freedom puts a spotlight on the conviction of innocent men with no evidence except the lying testimony of jailhouse snitches who have been coerced and given favors by cops and prosecutors.

Sex for Lies and Manufactured Testimony

For thirty-five years Major Tillery has fought against his 1983 arrest, then conviction and sentence of life imprisonment without parole for an unsolved 1976 pool hall murder and assault. Major Tillery's defense has always been his innocence. The police and prosecution knew Tillery did not commit these crimes. Jailhouse informant Emanuel Claitt gave lying testimony that Tillery was one of the shooters.

Homicide detectives and prosecutors threatened Claitt with a false unrelated murder charge, and induced him to lie with promises of little or no jail time on over twenty pending felonies, and being released from jail despite a parole violation. In addition, homicide detectives arranged for Claitt, while in custody, to have private sexual liaisons with his girlfriends in police interview rooms.

In May and June 2016, Emanuel Claitt gave sworn statements that his testimony was a total lie, and that the homicide cops and the prosecutors told him what to say and coached him before trial. Not only was he coerced to lie that Major Tillery was a shooter, but to lie and claim there were no plea deals made in exchange for his testimony. He provided the information about the specific homicide detectives and prosecutors involved in manufacturing his testimony and details about being allowed "sex for lies". In August 2016, Claitt reaffirmed his sworn statements in a videotape, posted on YouTube and on JusticeforMajorTillery.org.

Without the coerced and false testimony of Claitt there was no evidence against Major Tillery. There were no ballistics or any other physical evidence linking him to the shootings. The surviving victim's statement naming others as the shooters was not allowed into evidence.

The trial took place in May 1985 during the last days of the siege and firebombing of the MOVE family Osage Avenue home in Philadelphia that killed 13 Black people, including 5 children. The prosecution claimed that Major Tillery was part of an organized crime group, and falsely described it as run by the Nation of Islam. This prejudiced and inflamed the majority white jury against Tillery, to make up for the absence of any evidence that Tillery was involved in the shootings.

This was a frame-up conviction from top to bottom. Claitt was the sole or primary witness in five other murder cases in the early 1980s. Coercing and inducing jailhouse informants to falsely testify is a standard routine in criminal prosecutions. It goes hand in hand with prosecutors suppressing favorable evidence from the defense.

Major Tillery has filed a petition based on his actual innocence to the Philadelphia District Attorney's Larry Krasner's Conviction Review Unit. A full review and investigation should lead to reversal of Major Tillery's conviction. He also asks that the DA's office to release the full police and prosecution files on his case under the new "open files" policy. In the meantime, Major Tillery continues his own investigation. He needs your support.

Major Tillery has Fought his Conviction and Advocated for Other Prisoners for over 30 Years

The Pennsylvania courts have rejected three rounds of appeals challenging Major Tillery's conviction based on his innocence, the prosecution's intentional presentation of false evidence against him and his trial attorney's conflict of interest. On June 15, 2016 Major Tillery filed a new post-conviction petition based on the same evidence now in the petition to the District Attorney's Conviction Review Unit. Despite the written and video-taped statements from Emanuel Claitt that that his testimony against Major Tillery was a lie and the result of police and prosecutorial misconduct, Judge Leon Tucker dismissed Major Tillery's petition as "untimely" without even holding a hearing. Major Tillery appealed that dismissal and the appeal is pending in the Superior Court.

During the decades of imprisonment Tillery has advocated for other prisoners challenging solitary confinement, lack of medical and mental health care and the inhumane conditions of imprisonment. In 1990, he won the lawsuit, Tillery v. Owens, that forced the PA Department of Corrections (DOC) to end double celling (4 men to a small cell) at SCI Pittsburgh, which later resulted in the closing and then "renovation" of that prison.

Three years ago Major Tillery stood up for political prisoner and journalist Mumia Abu-Jamal and demanded prison Superintendent John Kerestes get Mumia to a hospital because "Mumia is dying." For defending Mumia and advocating for medical treatment for himself and others, prison officials retaliated. Tillery was shipped out of SCI Mahanoy, where Mumia was also held, to maximum security SCI Frackville and then set-up for a prison violation and a disciplinary penalty of months in solitary confinement. See, Messing with Major by Mumia Abu-Jamal. Major Tillery's federal lawsuit against the DOC for that retaliation is being litigated. Major Tillery continues as an advocate for all prisoners. He is fighting to get the DOC to establish a program for elderly prisoners.

Major Tillery Needs Your Help:

Well-known criminal defense attorney Stephen Patrizio represents Major pro bonoin challenging his conviction. More investigation is underway. We can't count on the district attorney's office to make the findings of misconduct against the police detectives and prosecutors who framed Major without continuing to dig up the evidence.

Major Tillery is now 67 years old. He's done hard time, imprisoned for almost 35 years, some 20 years in solitary confinement in max prisons for a crime he did not commit. He recently won hepatitis C treatment, denied to him for a decade by the DOC. He has severe liver problems as well as arthritis and rheumatism, back problems, and a continuing itchy skin rash. Within the past couple of weeks he was diagnosed with an extremely high heartbeat and is getting treatment.

Major Tillery does not want to die in prison. He and his family, daughters, sons and grandchildren are fighting to get him home. The newly filed petition for Conviction Review to the Philadelphia District Attorney's office lays out the evidence Major Tillery has uncovered, evidence suppressed by the prosecution through all these years he has been imprisoned and brought legal challenges into court. It is time for the District Attorney's to act on the fact that Major Tillery is innocent and was framed by police detectives and prosecutors who manufactured the evidence to convict him. Major Tillery's conviction should be vacated and he should be freed.

Major Tillery and family

HOW YOU CAN HELP

Financial Support—Tillery's investigation is ongoing. He badly needs funds to fight for his freedom.

Go to JPay.com;

code: Major Tillery AM9786 PADOC

Tell Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner:

The Conviction Review Unit should investigate Major Tillery's case. He is innocent. The only evidence at trial was from lying jail house informants who now admit it was false.

Call: 215-686-8000 or

Email: justice@phila.gov

Write to:

Security Processing Center

Major Tillery AM 9786

268 Bricker Road

Bellefonte, PA 16823

For More Information, Go To: JusticeForMajorTillery.org

Call/Write:

Kamilah Iddeen (717) 379-9009, Kamilah29@yahoo.com

Rachel Wolkenstein (917) 689-4009, RachelWolkenstein@gmail.com

Obtain Updates: www.justice4majortillery.info

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Free Leonard Peltier!

Art by Leonard Peltier

Write to:

Leonard Peltier 89637-132

USP Coleman 1, P.O. Box 1033

Coleman, FL 33521

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

1) We Are All Riders on the Same Planet

|

Listen and subscribe to our podcast from your mobile device: Via Apple Podcasts | Via RadioPublic | Via Stitcher

The sole survivor of an attack in which four people were murdered identified the perpetrators as three white men. The police ignored suspects who fit the description and arrested a young black man instead. He is now awaiting execution.

On today's episode:

• Kevin Cooper, who has been on death row at San Quentin State Prison in California for three decades.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Last week I met with fellow organizers and members of Mijente to take joint action at the Tornillo Port of Entry, where detention camps have been built and where children and adults are currently being imprisoned.

I oppose the hyper-criminalization of migrants and asylum seekers. Migration is a human right and every person is worthy of dignity and respect irrespective of whether they have "papers" or not. You shouldn't have to prove "extreme and unusual hardship" to avoid being separated from your family. We, as a country, have a moral responsibility to support and uplift those adversely affected by the US's decades-long role in the economic and military destabilization of the home countries these migrants and asylum seekers have been forced to leave.

While we expected to face resistance and potential trouble from the multiple law enforcement agencies represented at the border, we didn't expect to have a local farm hand pull a pistol on us to demand we deflate our giant balloon banner. Its message to those in detention:

NO ESTÁN SOLOS (You are not alone).

Despite the slight disruption to our plan we were able to support Mijente and United We Dream in blocking the main entrance to the detention camp and letting those locked inside know that there are people here who care for them and want to see them free and reunited with their families.

We are continuing to stand in solidarity with Mijente as they fight back against unjust immigration practices.Yesterday they took action in San Diego, continuing to lead and escalate resistance to unjust detention, Attorney General Jeff Sessions and to ICE.

While we were honored to offer on-the-ground support we see the potential to focus the energy of our Drop the MIC campaign into fighting against this injustice, to have an even greater impact. Here's how:

- Call out General Dynamics for profiteering of War, Militarization of the Border and Child and Family Detention (look for our social media toolkit this week);

- Create speaking forums and produce media that challenges the narrative of ICE and Jeff Sessions, encouraging troops who have served in the borderlands to speak out about that experience;

- Continue to show up and demand we demilitarize the border and abolish ICE.

Thank you for your vision and understanding of how militarism, racism, and capitalism are coming together in the most destructive ways. Help keep us in this fight by continuing to support our work.

In Solidarity,

Ramon Mejia

Field Organizer, About Face: Veterans Against the War

P.O. Box 3565, New York, NY 10008. All Right Reserved. | Unsubscribe

To ensure delivery of About Face emails please add webmaster@ivaw.org to your address book.

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Major George Tillery

MAJOR TILLERY FILES NEW LEGAL PETITION

SEX FOR LIES AND

MANUFACTURED TESTIMONY

|

April 25, 2018-- The arrest of two young men in Starbucks for the crime of "sitting while black," and the four years prison sentence to rapper Meek Mill for a minor parole violation are racist outrages in Philadelphia, PA that made national news in the past weeks. Yesterday Meek Mills was released on bail after a high profile defense campaign and a Pa Supreme Court decision citing evidence his conviction was based solely on a cop's false testimony.

These events underscore the racism, frame-up, corruption and brutality at the core of the criminal injustice system. Pennsylvania "lifer" Major Tillery's fight for freedom puts a spotlight on the conviction of innocent men with no evidence except the lying testimony of jailhouse snitches who have been coerced and given favors by cops and prosecutors.

Sex for Lies and Manufactured Testimony

For thirty-five years Major Tillery has fought against his 1983 arrest, then conviction and sentence of life imprisonment without parole for an unsolved 1976 pool hall murder and assault. Major Tillery's defense has always been his innocence. The police and prosecution knew Tillery did not commit these crimes. Jailhouse informant Emanuel Claitt gave lying testimony that Tillery was one of the shooters.

Homicide detectives and prosecutors threatened Claitt with a false unrelated murder charge, and induced him to lie with promises of little or no jail time on over twenty pending felonies, and being released from jail despite a parole violation. In addition, homicide detectives arranged for Claitt, while in custody, to have private sexual liaisons with his girlfriends in police interview rooms.

In May and June 2016, Emanuel Claitt gave sworn statements that his testimony was a total lie, and that the homicide cops and the prosecutors told him what to say and coached him before trial. Not only was he coerced to lie that Major Tillery was a shooter, but to lie and claim there were no plea deals made in exchange for his testimony. He provided the information about the specific homicide detectives and prosecutors involved in manufacturing his testimony and details about being allowed "sex for lies". In August 2016, Claitt reaffirmed his sworn statements in a videotape, posted on YouTube and on JusticeforMajorTillery.org.

Without the coerced and false testimony of Claitt there was no evidence against Major Tillery. There were no ballistics or any other physical evidence linking him to the shootings. The surviving victim's statement naming others as the shooters was not allowed into evidence.

The trial took place in May 1985 during the last days of the siege and firebombing of the MOVE family Osage Avenue home in Philadelphia that killed 13 Black people, including 5 children. The prosecution claimed that Major Tillery was part of an organized crime group, and falsely described it as run by the Nation of Islam. This prejudiced and inflamed the majority white jury against Tillery, to make up for the absence of any evidence that Tillery was involved in the shootings.

This was a frame-up conviction from top to bottom. Claitt was the sole or primary witness in five other murder cases in the early 1980s. Coercing and inducing jailhouse informants to falsely testify is a standard routine in criminal prosecutions. It goes hand in hand with prosecutors suppressing favorable evidence from the defense.

Major Tillery has filed a petition based on his actual innocence to the Philadelphia District Attorney's Larry Krasner's Conviction Review Unit. A full review and investigation should lead to reversal of Major Tillery's conviction. He also asks that the DA's office to release the full police and prosecution files on his case under the new "open files" policy. In the meantime, Major Tillery continues his own investigation. He needs your support.

Major Tillery has Fought his Conviction and Advocated for Other Prisoners for over 30 Years

The Pennsylvania courts have rejected three rounds of appeals challenging Major Tillery's conviction based on his innocence, the prosecution's intentional presentation of false evidence against him and his trial attorney's conflict of interest. On June 15, 2016 Major Tillery filed a new post-conviction petition based on the same evidence now in the petition to the District Attorney's Conviction Review Unit. Despite the written and video-taped statements from Emanuel Claitt that that his testimony against Major Tillery was a lie and the result of police and prosecutorial misconduct, Judge Leon Tucker dismissed Major Tillery's petition as "untimely" without even holding a hearing. Major Tillery appealed that dismissal and the appeal is pending in the Superior Court.

During the decades of imprisonment Tillery has advocated for other prisoners challenging solitary confinement, lack of medical and mental health care and the inhumane conditions of imprisonment. In 1990, he won the lawsuit, Tillery v. Owens, that forced the PA Department of Corrections (DOC) to end double celling (4 men to a small cell) at SCI Pittsburgh, which later resulted in the closing and then "renovation" of that prison.

Three years ago Major Tillery stood up for political prisoner and journalist Mumia Abu-Jamal and demanded prison Superintendent John Kerestes get Mumia to a hospital because "Mumia is dying." For defending Mumia and advocating for medical treatment for himself and others, prison officials retaliated. Tillery was shipped out of SCI Mahanoy, where Mumia was also held, to maximum security SCI Frackville and then set-up for a prison violation and a disciplinary penalty of months in solitary confinement. See, Messing with Major by Mumia Abu-Jamal. Major Tillery's federal lawsuit against the DOC for that retaliation is being litigated. Major Tillery continues as an advocate for all prisoners. He is fighting to get the DOC to establish a program for elderly prisoners.

Major Tillery Needs Your Help:

Well-known criminal defense attorney Stephen Patrizio represents Major pro bonoin challenging his conviction. More investigation is underway. We can't count on the district attorney's office to make the findings of misconduct against the police detectives and prosecutors who framed Major without continuing to dig up the evidence.

Major Tillery is now 67 years old. He's done hard time, imprisoned for almost 35 years, some 20 years in solitary confinement in max prisons for a crime he did not commit. He recently won hepatitis C treatment, denied to him for a decade by the DOC. He has severe liver problems as well as arthritis and rheumatism, back problems, and a continuing itchy skin rash. Within the past couple of weeks he was diagnosed with an extremely high heartbeat and is getting treatment.

Major Tillery does not want to die in prison. He and his family, daughters, sons and grandchildren are fighting to get him home. The newly filed petition for Conviction Review to the Philadelphia District Attorney's office lays out the evidence Major Tillery has uncovered, evidence suppressed by the prosecution through all these years he has been imprisoned and brought legal challenges into court. It is time for the District Attorney's to act on the fact that Major Tillery is innocent and was framed by police detectives and prosecutors who manufactured the evidence to convict him. Major Tillery's conviction should be vacated and he should be freed.

Obtain Updates: www.justice4majortillery.info

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

Free Leonard Peltier!

Art by Leonard Peltier

Write to:

Leonard Peltier 89637-132

USP Coleman 1, P.O. Box 1033

Coleman, FL 33521

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

|

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*---------*

1) We Are All Riders on the Same Planet

Seen from space 50 years ago, Earth appeared as a gift to preserve and cherish. What happened?

By Matthew Myer Boulton and Joseph Heithaus, December 24, 2018

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/24/opinion/earth-space-christmas-eve-apollo-8.html?action=click&module=Opinion&pgtype=Homepage